I’m very concerned about yesterday’s decision in U.S. v. Sabre, the antitrust case examining the merger of Sabre and Farelogix, two airline ticket software companies. Aside from the consolidation of the airline ticket software industry, the decision includes a really troubling interpretation of the already problematic American Express decision from 2018, potentially making it more difficult to challenge mergers involving dominant tech platforms.

You might remember the American Express (AmEx) decision from such very bad ideas as, “you can use benefits on one side of a two-sided market to justify harms to the other side.” Antitrust experts have been trying to overturn or at least minimize the impact of this no good very bad decision since it came out — including Public Knowledge advocating for Congress to clarify that it’s not a correct interpretation of the law, and others trying to socialize the narrow interpretation that it would only apply when the two supposed “sides” of the market are engaged in a single transaction. It’s also why we support bills like Senator Amy Klobuchar’s recently introduced exclusionary conduct bill that would get rid of the unnecessary market definition requirements imposed in AmEx that also hampered the Department of Justice in this case.

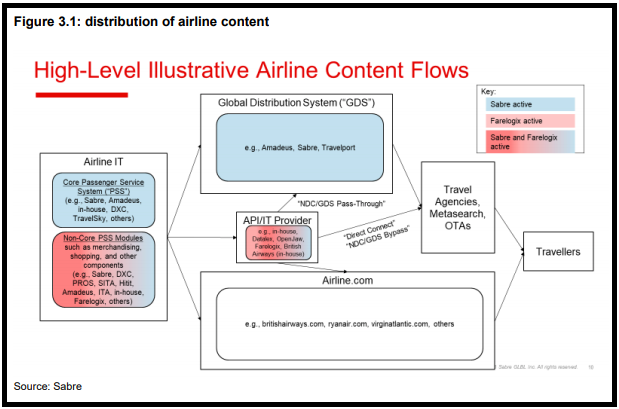

But Judge Leonard Stark is now using AmEx for a slightly different proposition. His idea is that a two-sided platform cannot, as a matter of law, compete with a company that operates on only one side of the market. The Court found Sabre to be a two-sided platform facilitating transactions between airlines and travel agencies. When a travel agency—whether it be a site like Expedia or a brick-and-mortar store—receives a client request for a flight, they use a Sabre system to browse flight options from the airlines. Sabre collects fees from airlines to both aggregate and create offers to travel agencies, which are then incentivized to use Sabre through incentive payments from them. Farelogix, an innovator in the field, developed a system to cut out the Sabre middleman. Farelogix sells a software suite to airlines allowing them to make their own offers either directly to travel agencies or on a Sabre platform. The Court interpreted these market facts to define Sabre as a two-sided platform (airlines to Sabre, Sabre to travel agencies), whereas Farelogix was only a competitor on one side of that market (the airline side).

A different court could have relied on the plethora of incriminating facts in the Department of Justice merger challenge. There was evidence that the introduction of the Farelogix system had resulted in lower negotiated Sabre fees from the airlines and internal Sabre documents and testimony showed that Sabre viewed Farelogix as a disruptive and innovative competitor capping its revenues. Instead, Judge Stark merely relied on a questionable proposition he gleaned from AmEx; since Farelogix does not compete on the travel agency side of the market, it could not be viewed as a Sabre competitor, end of story.

What is a two-sided market?

An important part of the platform competition discussion is the concept of a two-sided market. This is notoriously ill-defined, but in theory it’s a market where a platform connects two different types of customers. The American Express example was that a credit card is connecting businesses on one side, competing with each other, and customers on the other side, competing with each other. Amazon’s Marketplace is another two-sided platform, connecting retailers on one side with customers on the other. A different sort of two-sided market might be the Google search engine, where advertisers compete to show their ads in response to users doing searches. But this may show you how the theory starts to break down. Why isn’t CVS, or any retailer, a two-sided market? It’s connecting manufacturers with customers. Or any distributor could be called a two-sided market — they’re connecting manufacturers on one side with retailers on the other side. This shows one reason that we can’t have special antitrust laws only for two-sided markets. Any company will try to argue that it deserves the protections afforded companies in two-sided markets.

An Alternative View: The UK’s Competition & Markets Authority

Today, the UK’s competition authority, the CMA, released its final decision on the Sabre/Farelogix merger. The UK CMA recommends prohibiting the merger because it found the merger would cause a significant lessening of competition in both the travel agency and airline sides of the market. Using an exhibit created by Sabre itself, the CMA points out the areas where the two companies compete.

With Farelogix’s API cutting out Sabre as the platform middleman, Farelogix actually is exerting competitive pressure on the Sabre platform. From the perspective of travel agencies and airlines, Farelogix offers an alternative to much of what Sabre’s platform provides. In this way, Farelogix is a horizontal competitor.

Implications for Dominant Digital Platforms

Judge Stark’s new interpretation of AmEx, that a one-sided competitor can never exert competitive pressure on a two-sided firm, has especially concerning implications for some well-known frequent flyers at the antitrust agencies: the dominant digital platforms. Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Apple are all owners of two-sided platforms. It may be much harder for one-sided competitors to keep up with the power of a two-sided platform, but in markets that are not very competitive due to special economic characteristics, that type of rivalry is an important source of competitive pressure. While the vertical relationship (such as a supplier/distributor relationship) between a two-sided platform and a company that is only competing on one side of the platform may be more obvious, there is often a direct horizontal competition component to that relationship as well. And due to the current weakness of U.S. antitrust law in dealing with anticompetitive mergers and conduct between companies with a vertical relationship, it may be important in litigation to focus on the direct horizontal competition component.

For example, using Stark’s logic, Amazon could argue that it can buy a large ecommerce retailer because its Marketplace (a two-sided market) cannot face competition from a company that is only a retailer (one side of the market). Sure, all else being equal, a two-sided platform like Walmart’s Marketplace — which allows other retailers to sell on their site much like Amazon’s Marketplace–likely exerts stronger competitive pressure on Amazon than would a single ecommerce retailer of the same size, but a single ecommerce retailer also exerts some competitive pressure on Amazon. Depending on the size of the retailer, its ability to expand to challenge other platform services, and the level of concentration in the market, it may be enough competitive pressure that letting Amazon buy that retailer would be harmful and should be blocked.

It’s important that courts are able to assess these types of claims on the merits. There is no economic basis for Judge Stark’s presumption that a firm that participates in only one-side of the market can never exert competitive pressure on a two-sided firm. I’m hopeful this legal holding will be overturned on appeal. In the meantime, Congress should consider clarifying yet another way in which the AmEx decision may have been a departure from well-considered antitrust precedents and should be overturned.